Every school year feels like a new draft of a similar successful experiment. Four years into using Building Thinking Classrooms (BTC) strategies and I’m realizing that the best lessons aren’t just about math tasks, but about the habits, trust, and structure that make math thinking visible.

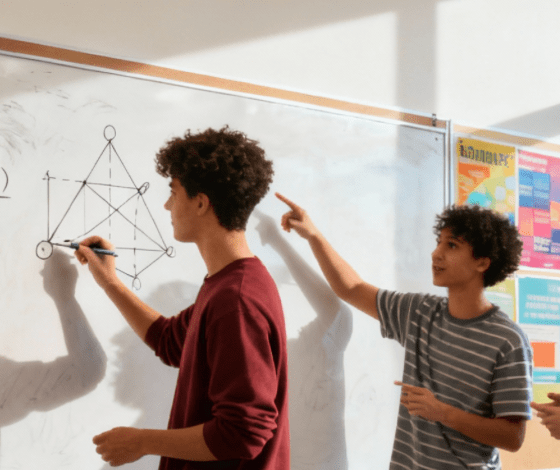

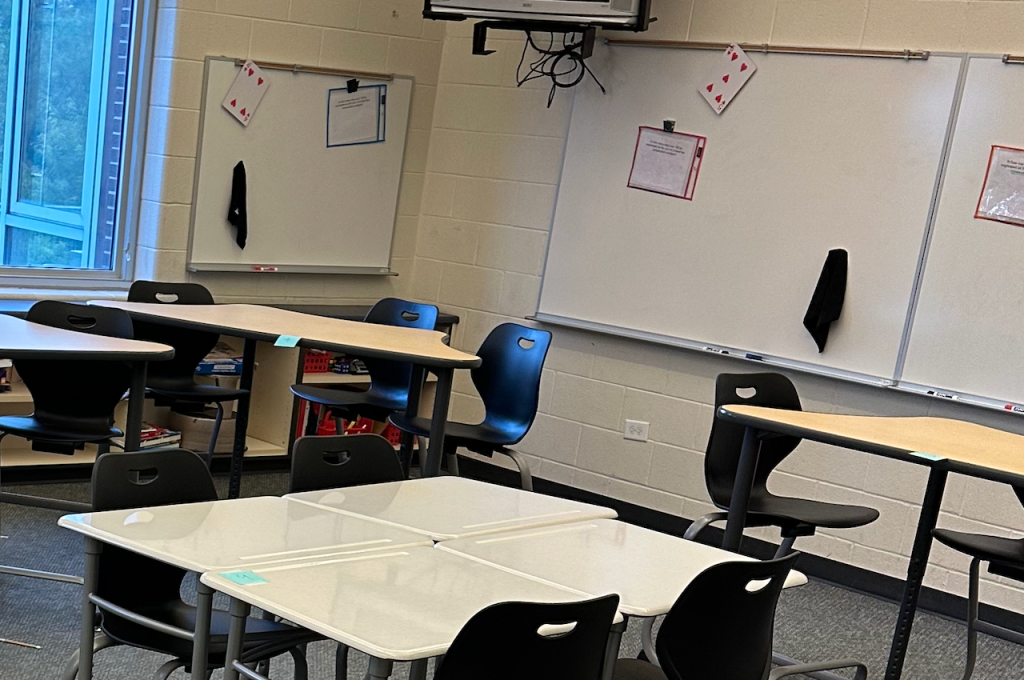

I started my BTC journey small: cutting shower panels purchased at Home Depot into makeshift whiteboards. Today, three of my four classroom walls are covered in the real thing and Expo markers are used daily. You could say I’ve gone all-in on getting students out of their seats and into mathematical conversations. It’s been one of the most worthwhile shifts in my teaching career. As with any change, I’ve hit plenty of bumps along the way. Here are a few lessons from trial and error:

- Vague directions lead to vague outcomes. Students need clarity to stay focused.

- Skipping norm reinforcement means classroom culture can unravel fast.

- Rigid time limits create stress instead of structure. Not every group works at the same pace.

When I forget these lessons, the classroom energy dips. But when the structure is clear and flexible, students take ownership. Through practice and reflection, I’ve found a few constants that make BTC thrive:

- Randomize groups every time. Students grow by learning with everyone, not just their usual partners.

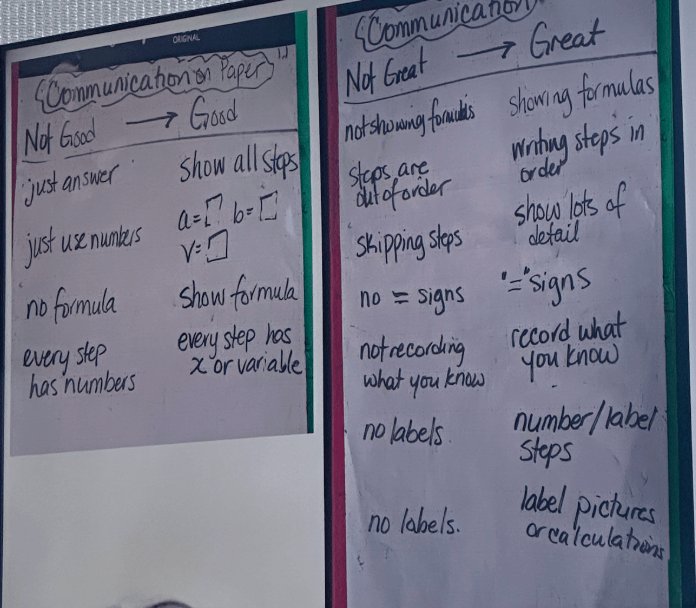

- Set clear expectations up front. Outline what happens during BTC time — how to collaborate, communicate, and close.

- Stay visible and present. Circulating, asking questions, and listening makes thinking public and valued.

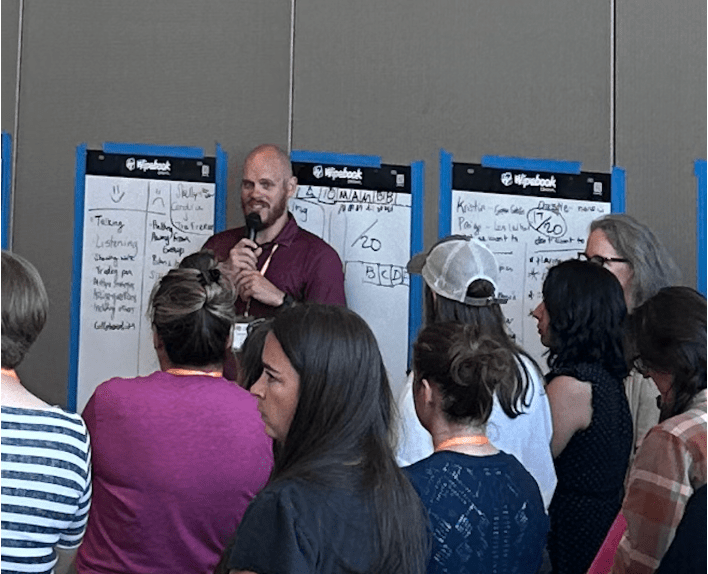

This year, I wanted to go a step further: to help students self-monitor their behavior and advocate for themselves while working at the boards. That goal took shape after attending the BTC Conference in Seattle this summer. One standout session, led by Idaho math teacher Nicholas Stevener explored how students can grade and norm themselves at the whiteboards.

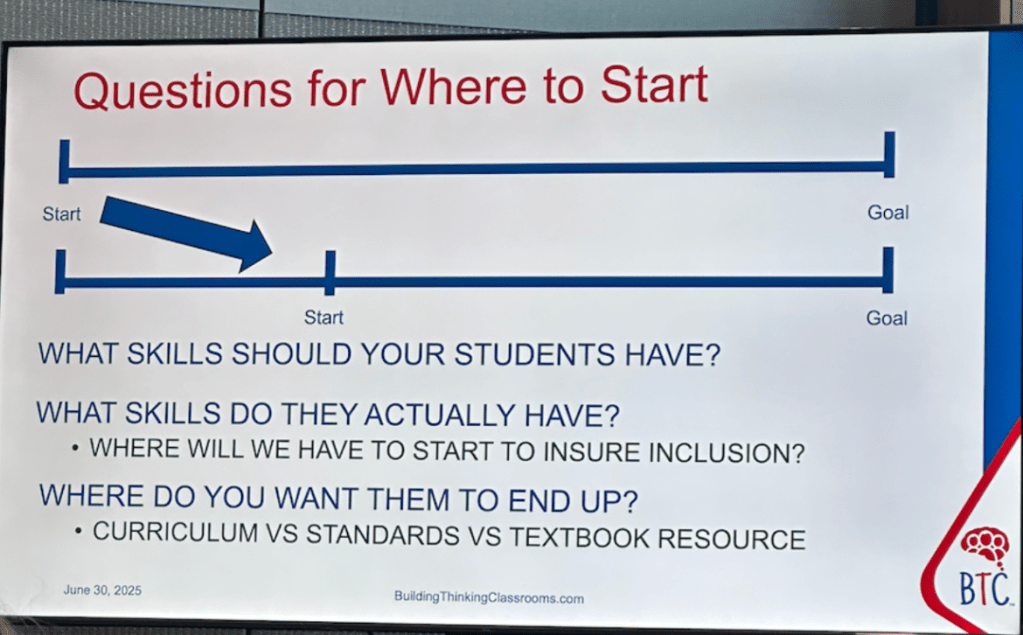

His simple coding system for reflection sparked an idea I wanted to bring home. After some non-curricular tasks to ease students into BTC routines, my sixth graders and I co-created classroom norms. Then, I introduced a self-monitoring tool called the MRC system:

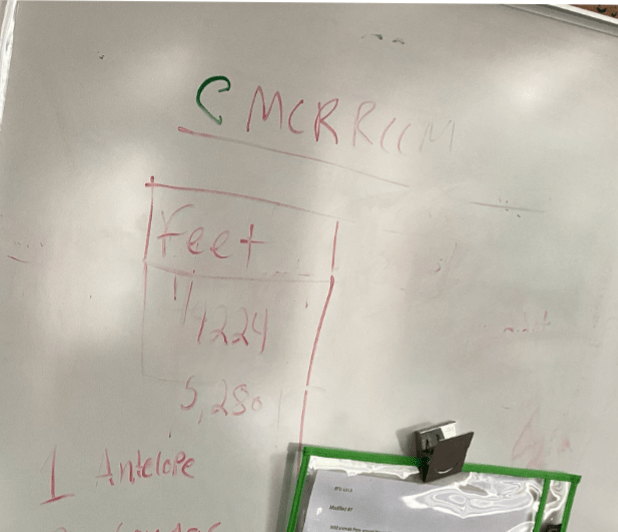

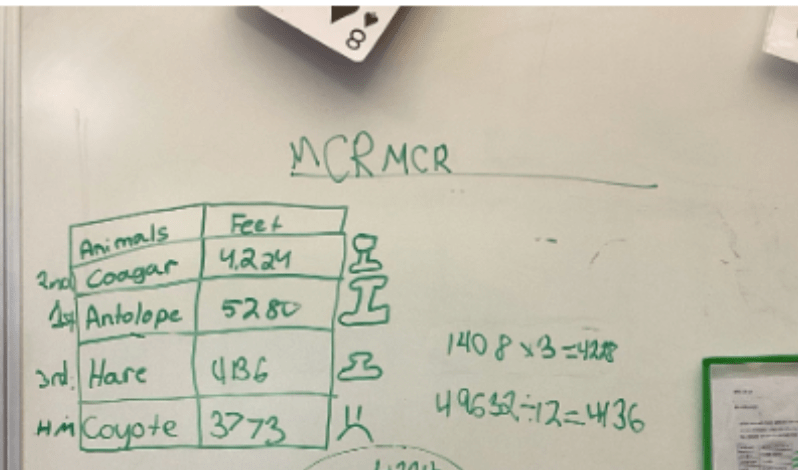

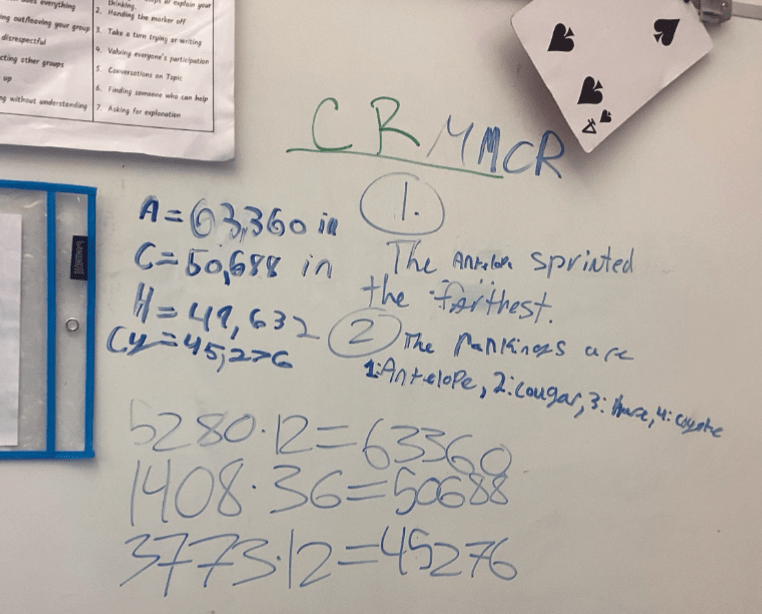

- At the start of whiteboard time, students draw a line across the top of their board.

- As they work, they add letters that describe their behavior:

- M for Marker — Are we sharing the marker?

- R for Respect — Are we speaking and listening respectfully?

- C for Collaboration — Are we working closely together?

Originally, I used “K” for kindness, but “Respect” offered a broader more reflective lens. As students work, I circulate and add letters too. If a group is showing strong teamwork, I’ll add a “C” If I notice they’ve drifted off track, I draw a small line and place a letter to the left — a quiet cue to refocus. It’s not designed to be punitive. It’s communication without interruption.

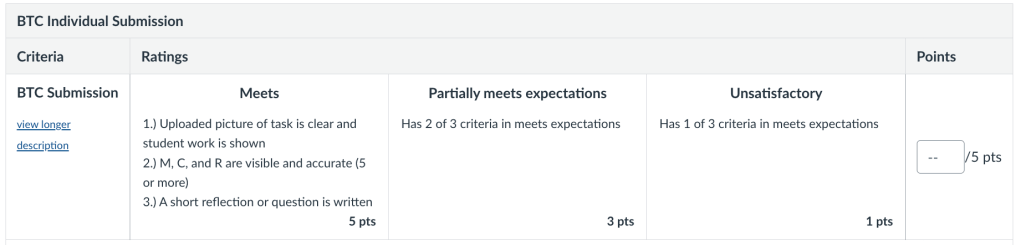

So far students see how their behavior evolves in real time. When whiteboard time ends, they snap a photo and submit it through Apple Classroom or Canvas. Their board becomes both a math artifact and a reflection tool.

The MRC system is still new, but it’s already doing what I hoped with helping students build awareness and action. BTC has always been about engagement, but this layer adds reflection and accountability too. I plan to refine the rubric over time, but I’m already seeing the difference: students are more thoughtful about how they learn, not just what they learn.

Teaching with BTC continues to remind me that structure and autonomy don’t have to compete. They can complement each other. When students understand what it means to contribute, respect, and collaborate, the math takes care of itself.

Written by Matt Coaty, a 6th grade math teacher in Illinois exploring ways to make student thinking visible through Building Thinking Classrooms.