Image by: J. Creationz

Having math reasoning skills is important. Generally, math reasoning skills are taught and incorporated in early elementary school. In math, a problem is what a student is asked and expected to answer. If a student is unable to answer why their answer is correct, I believe that the student might not fully grasp the mathematical concept. The student might not be utilizing math reasoning skills.

For example, a student that measures area in linear feet might not completely have an understanding that area is measured in square units. The student could have the correct numerical answer, but include the wrong unit (centimeters compared to square centimeters).

How is mathematical reasoning taught? I’m going to be taking a proactive step next year to give opportunities for my students to utilize math reasoning. I’m deciding to use higher level questioning to enable students to think of the process in finding the solution. The learning process is key. I’ve found that math instruction isn’t always linear, just as mathematical reasoning isn’t rigid. By asking students why/how they arrived at a solution is vital in understanding their thinking.

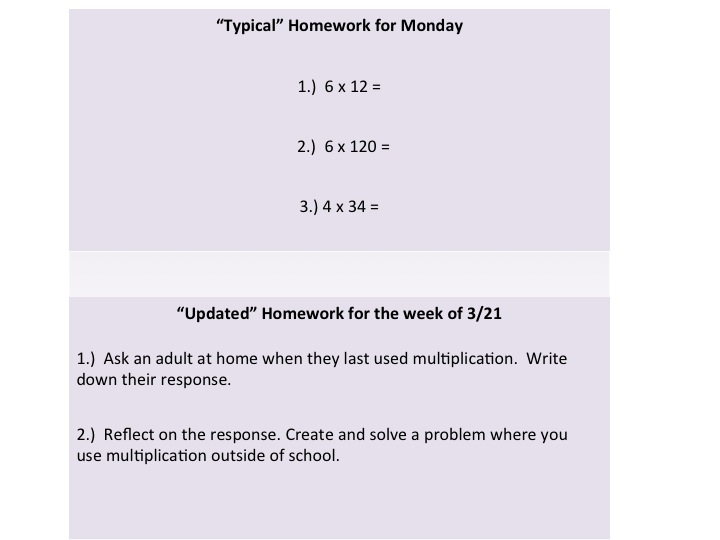

As I’m planning for next school year, I’ve decided to ask students to explain their reasoning more frequently. By hearing their reasoning, I’m in a better position to give direct feedback. All math questions have some type of reasoning. I believe that multiple solution / open-ended questions can be used to display mathematical reasoning. Students need to be able to explain why they responded with a specific answer and what methods/connections were utilized to solve the problem. Based on the math Common Core, students are expected to reason abstractly and quantitatively. When students describe their mathematical process, teachers are better able to diagnose and assess a student’s current level of understanding. Math reasoning isn’t always quantifiable, but it can be documented via journaling and other communication methods. More importantly, teachers will be able to provide specific feedback to help a student understand concepts more clearly. I also feel that this questioning process develops self-confidence in students and prepares them to become more responsible for their own learning. See the chart below.