I’ve been exploring the use of multiple solution problems in my math classes. These types of problems often ask students to think critically and explain their mathematical processes thoroughly. To be honest, these questions can be challenging for elementary students. Most younger students expect or have been accustomed to finding one right answer throughout their academic career. Unfortunately, state and local standardized assessments often encourage this type of behavior through multiple choice questions. This type of answer hunting can lead to limited explanations and more of a focus on only one mathematical strategy, therefore emphasizing test-taking strategies. Encouraging students to hunt for only the answer often becomes a detriment to the learning process over time. Moving beyond getting the one right answer should be encouraged and modeled. Bruce Ferrington’s post on quality over quantity displays how the Japanese encourage multiple solutions and strategies to solve problems. This type of instruction seems to delve more into the problem solving properties of mathematics. Using this model, I decided to do something similar with my students.

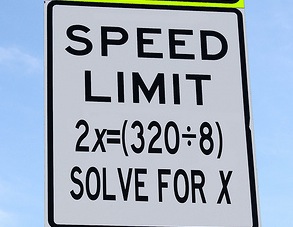

I gave the following problem to the students:

How do you find the area of the octagon below? Explain the steps and formulas that you used to solve the problem.

At first many students had questions. The questions started out as procedural direction clarification and then started down the path of a) how much writing is required? b) how many points is this worth? c) how many steps are involved? d) Is there one right answer? I eventually stopped the class and asked them to explain their method to find the area of the octagon, basically restating the question. I also mentioned that they could use any of the formulas that we’ve discussed in class. Still, more questions ensued. Instead of answering their questions, I decided to propose a question back to them inorder to encourage independent mathematical thinking. Here are a few of the Q and A’s that took place:

SQ = Student Question TA = Teacher Answer

SQ: Where do I start?

TA: What formulas have you learned that will help you in this problem?

SQ: Do I need to solve for x?

TA: Does the question ask for you to solve for x?

SQ: Should I split up the octagon into different parts?

TA: Do you think splitting up the octagon will help you?

SQ: How do I know if the triangle is a right angle?

TA: What have we learned about angle properties to help you answer that question?

Eventually, students began to think more about the mathematical process and less about finding an exact answer. This evolution in problem solving was inspiring. Students began to ask less questions and explain more of their thinking on paper. At the end of the math session students were asked to present their answers. It became apparent that there were multiple methods to solve the problem. Even more important, students started to understand that their perseverance was contributing to their success. The answer in itself was not the main goal, but the mathematical thinking was emphasized throughout the process.

Afterwards, students were asked to complete a math journal entry on how they felt about the activity.

Image Credit: Kreeti